The Free Lunch Is Over

A Fundamental Turn Toward Concurrency in Software

By Herb SutterThe biggest sea change in software development since the OO revolution is knocking at the door, and its name is Concurrency.

This article appeared in Dr. Dobb's Journal, 30(3), March 2005. A much briefer version under the title "The Concurrency Revolution" appeared in C/C++ Users Journal, 23(2), February 2005.

Update note: The CPU trends graph last updated August 2009 to include current

data and show the trend continues as predicted. The rest of this article

including all text is still original as first posted here in December 2004.

Your free lunch will soon be over. What can you do about it? What are you doing about it?

The

major processor manufacturers and architectures, from Intel and AMD to

Sparc and PowerPC, have run out of room with most of their traditional

approaches to boosting CPU performance. Instead of driving clock speeds

and straight-line instruction throughput ever higher, they are instead

turning en masse to hyperthreading and multicore architectures.

Both of these features are already available on chips today; in

particular, multicore is available on current PowerPC and Sparc IV

processors, and is coming in 2005 from Intel and AMD. Indeed, the big

theme of the 2004 In-Stat/MDR Fall Processor Forum was multicore

devices, as many companies showed new or updated multicore processors.

Looking back, it’s not much of a stretch to call 2004 the year of

multicore.

And that puts

us at a fundamental turning point in software development, at least for

the next few years and for applications targeting general-purpose

desktop computers and low-end servers (which happens to account for the

vast bulk of the dollar value of software sold today). In this article,

I’ll describe the changing face of hardware, why it suddenly does matter

to software, and how specifically the concurrency revolution matters to

you and is going to change the way you will likely be writing software

in the future.

Arguably, the free lunch has already been over for a year or two, only we’re just now noticing.

The Free Performance Lunch

There’s

an interesting phenomenon that’s known as “Andy giveth, and Bill taketh

away.” No matter how fast processors get, software consistently finds

new ways to eat up the extra speed. Make a CPU ten times as fast, and

software will usually find ten times as much to do (or, in some cases,

will feel at liberty to do it ten times less efficiently). Most classes

of applications have enjoyed free and regular performance gains for

several decades, even without releasing new versions or doing anything

special, because the CPU manufacturers (primarily) and memory and disk

manufacturers (secondarily) have reliably enabled ever-newer and

ever-faster mainstream systems. Clock speed isn’t the only measure of

performance, or even necessarily a good one, but it’s an instructive

one: We’re used to seeing 500MHz CPUs give way to 1GHz CPUs give way to

2GHz CPUs, and so on. Today we’re in the 3GHz range on mainstream

computers.

The key

question is: When will it end? After all, Moore’s Law predicts

exponential growth, and clearly exponential growth can’t continue

forever before we reach hard physical limits; light isn’t getting any

faster. The growth must eventually slow down and even end. (Caveat: Yes,

Moore’s Law applies principally to transistor densities, but the same

kind of exponential growth has occurred in related areas such as clock

speeds. There’s even faster growth in other spaces, most notably the

data storage explosion, but that important trend belongs in a different

article.)

If you’re a

software developer, chances are that you have already been riding the

“free lunch” wave of desktop computer performance. Is your application’s

performance borderline for some local operations? “Not to worry,” the

conventional (if suspect) wisdom goes; “tomorrow’s processors will have

even more throughput, and anyway today’s applications are increasingly

throttled by factors other than CPU throughput and memory speed (e.g.,

they’re often I/O-bound, network-bound, database-bound).” Right?

Right enough, in the past. But dead wrong for the foreseeable future.

The

good news is that processors are going to continue to become more

powerful. The bad news is that, at least in the short term, the growth

will come mostly in directions that do not take most current

applications along for their customary free ride.

Over

the past 30 years, CPU designers have achieved performance gains in

three main areas, the first two of which focus on straight-line

execution flow:

clock speed

| |

execution optimization

| |

cache

|

Increasing clock speed is

about getting more cycles. Running the CPU faster more or less directly

means doing the same work faster.

Optimizing

execution flow is about doing more work per cycle. Today’s CPUs sport

some more powerful instructions, and they perform optimizations that

range from the pedestrian to the exotic, including pipelining, branch

prediction, executing multiple instructions in the same clock cycle(s),

and even reordering the instruction stream for out-of-order execution.

These techniques are all designed to make the instructions flow better

and/or execute faster, and to squeeze the most work out of each clock

cycle by reducing latency and maximizing the work accomplished per clock

cycle.

Chip

designers are under so much pressure to deliver ever-faster CPUs that

they’ll risk changing the meaning of your program, and possibly break

it, in order to make it run faster

|

Brief

aside on instruction reordering and memory models: Note that some of

what I just called “optimizations” are actually far more than

optimizations, in that they can change the meaning of programs and cause

visible effects that can break reasonable programmer expectations. This

is significant. CPU designers are generally sane and well-adjusted

folks who normally wouldn’t hurt a fly, and wouldn’t think of hurting

your code… normally. But in recent years they have been willing to

pursue aggressive optimizations just to wring yet more speed out of each

cycle, even knowing full well that these aggressive rearrangements

could endanger the semantics of your code. Is this Mr. Hyde making an

appearance? Not at all. That willingness is simply a clear indicator of

the extreme pressure the chip designers face to deliver ever-faster

CPUs; they’re under so much pressure that they’ll risk changing the

meaning of your program, and possibly break it, in order to make it run

faster. Two noteworthy examples in this respect are write reordering and

read reordering: Allowing a processor to reorder write operations has

consequences that are so surprising, and break so many programmer

expectations, that the feature generally has to be turned off because

it’s too difficult for programmers to reason correctly about the meaning

of their programs in the presence of arbitrary write reordering.

Reordering read operations can also yield surprising visible effects,

but that is more commonly left enabled anyway because it isn’t quite as

hard on programmers, and the demands for performance cause designers of

operating systems and operating environments to compromise and choose

models that place a greater burden on programmers because that is viewed

as a lesser evil than giving up the optimization opportunities.

Finally,

increasing the size of on-chip cache is about staying away from RAM.

Main memory continues to be so much slower than the CPU that it makes

sense to put the data closer to the processor—and you can’t get much

closer than being right on the die. On-die cache sizes have soared, and

today most major chip vendors will sell you CPUs that have 2MB and more

of on-board L2 cache. (Of these three major historical approaches to

boosting CPU performance, increasing cache is the only one that will

continue in the near term. I’ll talk a little more about the importance

of cache later on.)

Okay. So what does this mean?

A

fundamentally important thing to recognize about this list is that all

of these areas are concurrency-agnostic. Speedups in any of these areas

will directly lead to speedups in sequential (nonparallel,

single-threaded, single-process) applications, as well as applications

that do make use of concurrency. That’s important, because the vast

majority of today’s applications are single-threaded, for good reasons

that I’ll get into further below.

Of

course, compilers have had to keep up; sometimes you need to recompile

your application, and target a specific minimum level of CPU, in order

to benefit from new instructions (e.g., MMX, SSE) and some new CPU

features and characteristics. But, by and large, even old applications

have always run significantly faster—even without being recompiled to

take advantage of all the new instructions and features offered by the

latest CPUs.

That world was a nice place to be. Unfortunately, it has already disappeared.

Obstacles, and Why You Don’t Have 10GHz Today

CPU performance growth as we have known it hit a wall two years ago. Most people have only recently started to notice.

You

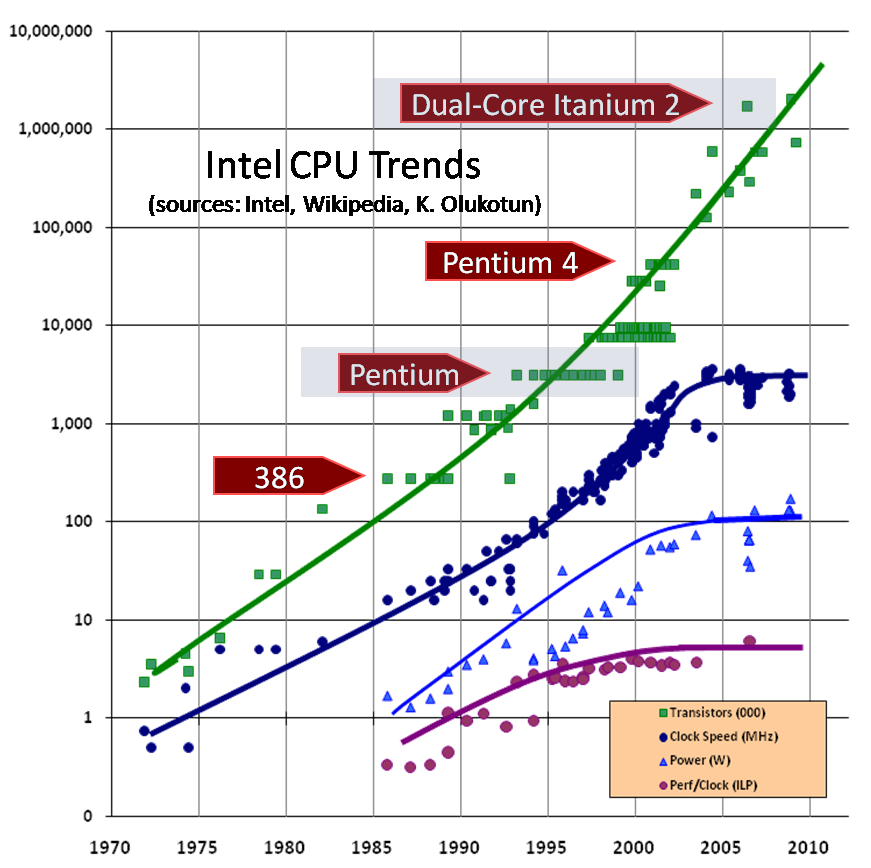

can get similar graphs for other chips, but I’m going to use Intel data

here. Figure 1 graphs the history of Intel chip introductions by clock

speed and number of transistors. The number of transistors continues to

climb, at least for now. Clock speed, however, is a different story.

Figure 1:

Intel CPU Introductions (graph updated August 2009; article text original

from December 2004)

|

Around the beginning of 2003,

you’ll note a disturbing sharp turn in the previous trend toward

ever-faster CPU clock speeds. I’ve added lines to show the limit trends

in maximum clock speed; instead of continuing on the previous path, as

indicated by the thin dotted line, there is a sharp flattening. It has

become harder and harder to exploit higher clock speeds due to not just

one but several physical issues, notably heat (too much of it and too

hard to dissipate), power consumption (too high), and current leakage

problems.

Quick: What’s

the clock speed on the CPU(s) in your current workstation? Are you

running at 10GHz? On Intel chips, we reached 2GHz a long time ago

(August 2001), and according to CPU trends before 2003, now in early

2005 we should have the first 10GHz Pentium-family chips. A quick look

around shows that, well, actually, we don’t. What’s more, such chips are

not even on the horizon—we have no good idea at all about when we might

see them appear.

Well,

then, what about 4GHz? We’re at 3.4GHz already—surely 4GHz can’t be far

away? Alas, even 4GHz seems to be remote indeed. In mid-2004, as you

probably know, Intel first delayed its planned introduction of a 4GHz

chip until 2005, and then in fall 2004 it officially abandoned its 4GHz

plans entirely. As of this writing, Intel is planning to ramp up a

little further to 3.73GHz in early 2005 (already included in Figure 1 as

the upper-right-most dot), but the clock race really is over, at least

for now; Intel’s and most processor vendors’ future lies elsewhere as

chip companies aggressively pursue the same new multicore directions.

We’ll

probably see 4GHz CPUs in our mainstream desktop machines someday, but

it won’t be in 2005. Sure, Intel has samples of their chips running at

even higher speeds in the lab—but only by heroic efforts, such as

attaching hideously impractical quantities of cooling equipment. You

won’t have that kind of cooling hardware in your office any day soon,

let alone on your lap while computing on the plane.

TANSTAAFL: Moore’s Law and the Next Generation(s)

“There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” —R. A. Heinlein, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress

Does

this mean Moore’s Law is over? Interestingly, the answer in general

seems to be no. Of course, like all exponential progressions, Moore’s

Law must end someday, but it does not seem to be in danger for a few

more years yet. Despite the wall that chip engineers have hit in juicing

up raw clock cycles, transistor counts continue to explode and it seems

CPUs will continue to follow Moore’s Law-like throughput gains for some

years to come.

|

The

key difference, which is the heart of this article, is that the

performance gains are going to be accomplished in fundamentally

different ways for at least the next couple of processor generations.

And most current applications will no longer benefit from the free ride

without significant redesign.

For

the near-term future, meaning for the next few years, the performance

gains in new chips will be fueled by three main approaches, only one of

which is the same as in the past. The near-term future performance

growth drivers are:

hyperthreading

| |

multicore

| |

cache

|

Hyperthreading is about

running two or more threads in parallel inside a single CPU.

Hyperthreaded CPUs are already available today, and they do allow some

instructions to run in parallel. A limiting factor, however, is that

although a hyper-threaded CPU has some extra hardware including extra

registers, it still has just one cache, one integer math unit, one FPU,

and in general just one each of most basic CPU features. Hyperthreading

is sometimes cited as offering a 5% to 15% performance boost for

reasonably well-written multi-threaded applications, or even as much as

40% under ideal conditions for carefully written multi-threaded

applications. That’s good, but it’s hardly double, and it doesn’t help

single-threaded applications.

Multicore

is about running two or more actual CPUs on one chip. Some chips,

including Sparc and PowerPC, have multicore versions available already.

The initial Intel and AMD designs, both due in 2005, vary in their level

of integration but are functionally similar. AMD’s seems to have some

initial performance design advantages, such as better integration of

support functions on the same die, whereas Intel’s initial entry

basically just glues together two Xeons on a single die. The performance

gains should initially be about the same as having a true dual-CPU

system (only the system will be cheaper because the motherboard doesn’t

have to have two sockets and associated “glue” chippery), which means

something less than double the speed even in the ideal case, and just

like today it will boost reasonably well-written multi-threaded

applications. Not single-threaded ones.

Finally,

on-die cache sizes can be expected to continue to grow, at least in the

near term. Of these three areas, only this one will broadly benefit

most existing applications. The continuing growth in on-die cache sizes

is an incredibly important and highly applicable benefit for many

applications, simply because space is speed. Accessing main memory is

expensive, and you really don’t want to touch RAM if you can help it. On

today’s systems, a cache miss that goes out to main memory often costs

10 to 50 times as much getting the information from the cache; this,

incidentally, continues to surprise people because we all think of

memory as fast, and it is fast compared to disks and networks, but not

compared to on-board cache which runs at faster speeds. If an

application’s working set fits into cache, we’re golden, and if it

doesn’t, we’re not. That is why increased cache sizes will save some

existing applications and breathe life into them for a few more years

without requiring significant redesign: As existing applications

manipulate more and more data, and as they are incrementally updated to

include more code for new features, performance-sensitive operations

need to continue to fit into cache. As the Depression-era old-timers

will be quick to remind you, “Cache is king.”

(Aside:

Here’s an anecdote to demonstrate “space is speed” that recently hit my

compiler team. The compiler uses the same source base for the 32-bit

and 64-bit compilers; the code is just compiled as either a 32-bit

process or a 64-bit one. The 64-bit compiler gained a great deal of

baseline performance by running on a 64-bit CPU, principally because the

64-bit CPU had many more registers to work with and had other code

performance features. All well and good. But what about data? Going to

64 bits didn’t change the size of most of the data in memory, except

that of course pointers in particular were now twice the size they were

before. As it happens, our compiler uses pointers much more heavily in

its internal data structures than most other kinds of applications ever

would. Because pointers were now 8 bytes instead of 4 bytes, a pure data

size increase, we saw a significant increase in the 64-bit compiler’s

working set. That bigger working set caused a performance penalty that

almost exactly offset the code execution performance increase we’d

gained from going to the faster processor with more registers. As of

this writing, the 64-bit compiler runs at the same speed as the 32-bit

compiler, even though the source base is the same for both and the

64-bit processor offers better raw processing throughput. Space is

speed.)

But cache is it. Hyperthreading and multicore CPUs will have nearly no impact on most current applications.

So

what does this change in the hardware mean for the way we write

software? By now you’ve probably noticed the basic answer, so let’s

consider it and its consequences.

What This Means For Software: The Next Revolution

In

the 1990s, we learned to grok objects. The revolution in mainstream

software development from structured programming to object-oriented

programming was the greatest such change in the past 20 years, and

arguably in the past 30 years. There have been other changes, including

the most recent (and genuinely interesting) naissance of web

services, but nothing that most of us have seen during our careers has

been as fundamental and as far-reaching a change in the way we write

software as the object revolution.

Until now.

Starting

today, the performance lunch isn’t free any more. Sure, there will

continue to be generally applicable performance gains that everyone can

pick up, thanks mainly to cache size improvements. But if you want your

application to benefit from the continued exponential throughput

advances in new processors, it will need to be a well-written concurrent

(usually multithreaded) application. And that’s easier said than done,

because not all problems are inherently parallelizable and because

concurrent programming is hard.

I

can hear the howls of protest: “Concurrency? That’s not news! People

are already writing concurrent applications.” That’s true. Of a small

fraction of developers.

Remember

that people have been doing object-oriented programming since at least

the days of Simula in the late 1960s. But OO didn’t become a revolution,

and dominant in the mainstream, until the 1990s. Why then? The reason

the revolution happened was primarily that our industry was driven by

requirements to write larger and larger systems that solved larger and

larger problems and exploited the greater and greater CPU and storage

resources that were becoming available. OOP’s strengths in abstraction

and dependency management made it a necessity for achieving large-scale

software development that is economical, reliable, and repeatable.

Concurrency is the next major revolution in how we write software

|

Similarly,

we’ve been doing concurrent programming since those same dark ages,

writing coroutines and monitors and similar jazzy stuff. And for the

past decade or so we’ve witnessed incrementally more and more

programmers writing concurrent (multi-threaded, multi-process) systems.

But an actual revolution marked by a major turning point toward

concurrency has been slow to materialize. Today the vast majority of

applications are single-threaded, and for good reasons that I’ll

summarize in the next section.

By

the way, on the matter of hype: People have always been quick to

announce “the next software development revolution,” usually about their

own brand-new technology. Don’t believe it. New technologies are often

genuinely interesting and sometimes beneficial, but the biggest

revolutions in the way we write software generally come from

technologies that have already been around for some years and have

already experienced gradual growth before they transition to explosive

growth. This is necessary: You can only base a software development

revolution on a technology that’s mature enough to build on (including

having solid vendor and tool support), and it generally takes any new

software technology at least seven years before it’s solid enough to be

broadly usable without performance cliffs and other gotchas. As a

result, true software development revolutions like OO happen around

technologies that have already been undergoing refinement for years,

often decades. Even in Hollywood, most genuine “overnight successes”

have really been performing for many years before their big break.

Concurrency

is the next major revolution in how we write software. Different

experts still have different opinions on whether it will be bigger than

OO, but that kind of conversation is best left to pundits. For

technologists, the interesting thing is that concurrency is of the same

order as OO both in the (expected) scale of the revolution and in the

complexity and learning curve of the technology.

Benefits and Costs of Concurrency

There

are two major reasons for which concurrency, especially multithreading,

is already used in mainstream software. The first is to logically

separate naturally independent control flows; for example, in a database

replication server I designed it was natural to put each replication

session on its own thread, because each session worked completely

independently of any others that might be active (as long as they

weren’t working on the same database row). The second and less common

reason to write concurrent code in the past has been for performance,

either to scalably take advantage of multiple physical CPUs or to easily

take advantage of latency in other parts of the application; in my

database replication server, this factor applied as well and the

separate threads were able to scale well on multiple CPUs as our server

handled more and more concurrent replication sessions with many other

servers.

There are,

however, real costs to concurrency. Some of the obvious costs are

actually relatively unimportant. For example, yes, locks can be

expensive to acquire, but when used judiciously and properly you gain

much more from the concurrent execution than you lose on the

synchronization, if you can find a sensible way to parallelize the

operation and minimize or eliminate shared state.

Perhaps

the second-greatest cost of concurrency is that not all applications

are amenable to parallelization. I’ll say more about this later on.

Probably

the greatest cost of concurrency is that concurrency really is hard:

The programming model, meaning the model in the programmer’s head that

he needs to reason reliably about his program, is much harder than it is

for sequential control flow.

Everybody

who learns concurrency thinks they understand it, ends up finding

mysterious races they thought weren’t possible, and discovers that they

didn’t actually understand it yet after all. As the developer learns to

reason about concurrency, they find that usually those races can be

caught by reasonable in-house testing, and they reach a new plateau of

knowledge and comfort. What usually doesn’t get caught in testing,

however, except in shops that understand why and how to do real stress

testing, is those latent concurrency bugs that surface only on true

multiprocessor systems, where the threads aren’t just being switched

around on a single processor but where they really do execute truly

simultaneously and thus expose new classes of errors. This is the next

jolt for people who thought that surely now they know how to write

concurrent code: I’ve come across many teams whose application worked

fine even under heavy and extended stress testing, and ran perfectly at

many customer sites, until the day that a customer actually had a real

multiprocessor machine and then deeply mysterious races and corruptions

started to manifest intermittently. In the context of today’s CPU

landscape, then, redesigning your application to run multithreaded on a

multicore machine is a little like learning to swim by jumping into the

deep end—going straight to the least forgiving, truly parallel

environment that is most likely to expose the things you got wrong. Even

when you have a team that can reliably write safe concurrent code,

there are other pitfalls; for example, concurrent code that is

completely safe but isn’t any faster than it was on a single-core

machine, typically because the threads aren’t independent enough and

share a dependency on a single resource which re-serializes the

program’s execution. This stuff gets pretty subtle.

The

vast majority of programmers today don’t grok concurrency, just as the

vast majority of programmers 15 years ago didn’t yet grok objects

|

Just

as it is a leap for a structured programmer to learn OO (what’s an

object? what’s a virtual function? how should I use inheritance? and

beyond the “whats” and “hows,” why are the correct design practices

actually correct?), it’s a leap of about the same magnitude for a

sequential programmer to learn concurrency (what’s a race? what’s a

deadlock? how can it come up, and how do I avoid it? what constructs

actually serialize the program that I thought was parallel? how is the

message queue my friend? and beyond the “whats” and “hows,” why are the

correct design practices actually correct?).

The

vast majority of programmers today don’t grok concurrency, just as the

vast majority of programmers 15 years ago didn’t yet grok objects. But

the concurrent programming model is learnable, particularly if we stick

to message- and lock-based programming, and once grokked it isn’t that

much harder than OO and hopefully can become just as natural. Just be

ready and allow for the investment in training and time, for you and for

your team.

(I

deliberately limit the above to message- and lock-based concurrent

programming models. There is also lock-free programming, supported most

directly at the language level in Java 5 and in at least one popular C++

compiler. But concurrent lock-free programming is known to be very much

harder for programmers to understand and reason about than even

concurrent lock-based programming. Most of the time, only systems and

library writers should have to understand lock-free programming,

although virtually everybody should be able to take advantage of the

lock-free systems and libraries those people produce. Frankly, even

lock-based programming is hazardous.)

What It Means For Us

Okay, back to what it means for us.

1. The clear primary consequence we’ve already covered is that applications will increasingly need to be concurrent if they want to fully exploit CPU throughput gains

that have now started becoming available and will continue to

materialize over the next several years. For example, Intel is talking

about someday producing 100-core chips; a single-threaded application

can exploit at most 1/100 of such a chip’s potential throughput. “Oh,

performance doesn’t matter so much, computers just keep getting faster”

has always been a naïve statement to be viewed with suspicion, and for

the near future it will almost always be simply wrong.

Applications will increasingly need to be concurrent if they want to fully exploit continuing exponential CPU throughput gains

Efficiency and performance optimization will get more, not less, important

|

Now,

not all applications (or, more precisely, important operations of an

application) are amenable to parallelization. True, some problems, such

as compilation, are almost ideally parallelizable. But others aren’t;

the usual counterexample here is that just because it takes one woman

nine months to produce a baby doesn’t imply that nine women could

produce one baby in one month. You’ve probably come across that analogy

before. But did you notice the problem with leaving the analogy at that?

Here’s the trick question to ask the next person who uses it on you:

Can you conclude from this that the Human Baby Problem is inherently not

amenable to parallelization? Usually people relating this analogy err

in quickly concluding that it demonstrates an inherently nonparallel

problem, but that’s actually not necessarily correct at all. It is

indeed an inherently nonparallel problem if the goal is to produce one

child. It is actually an ideally parallelizable problem if the goal is

to produce many children! Knowing the real goals can make all the

difference. This basic goal-oriented principle is something to keep in

mind when considering whether and how to parallelize your software.

2. Perhaps a less obvious consequence is that applications are likely to become increasingly CPU-bound.

Of course, not every application operation will be CPU-bound, and even

those that will be affected won’t become CPU-bound overnight if they

aren’t already, but we seem to have reached the end of the “applications

are increasingly I/O-bound or network-bound or database-bound” trend,

because performance in those areas is still improving rapidly (gigabit

WiFi, anyone?) while traditional CPU performance-enhancing techniques

have maxed out. Consider: We’re stopping in the 3GHz range for now.

Therefore single-threaded programs are likely not to get much faster any

more for now except for benefits from further cache size growth (which

is the main good news). Other gains are likely to be incremental and

much smaller than we’ve been used to seeing in the past, for example as

chip designers find new ways to keep pipelines full and avoid stalls,

which are areas where the low-hanging fruit has already been harvested.

The demand for new application features is unlikely to abate, and even

more so the demand to handle vastly growing quantities of application

data is unlikely to stop accelerating. As we continue to demand that

programs do more, they will increasingly often find that they run out of

CPU to do it unless they can code for concurrency.

There

are two ways to deal with this sea change toward concurrency. One is to

redesign your applications for concurrency, as above. The other is to

be frugal, by writing code that is more efficient and less wasteful.

This leads to the third interesting consequence:

3. Efficiency and performance optimization will get more, not less, important.

Those languages that already lend themselves to heavy optimization will

find new life; those that don’t will need to find ways to compete and

become more efficient and optimizable. Expect long-term increased demand

for performance-oriented languages and systems.

4. Finally, programming languages and systems will increasingly be forced to deal well with concurrency.

The Java language has included support for concurrency since its

beginning, although mistakes were made that later had to be corrected

over several releases in order to do concurrent programming more

correctly and efficiently. The C++ language has long been used to write

heavy-duty multithreaded systems well, but it has no standardized

support for concurrency at all (the ISO C++ standard doesn’t even

mention threads, and does so intentionally), and so typically the

concurrency is of necessity accomplished by using nonportable

platform-specific concurrency features and libraries. (It’s also often

incomplete; for example, static variables must be initialized only once,

which typically requires that the compiler wrap them with a lock, but

many C++ implementations do not generate the lock.) Finally, there are a

few concurrency standards, including pthreads and OpenMP, and some of

these support implicit as well as explicit parallelization. Having the

compiler look at your single-threaded program and automatically figure

out how to parallelize it implicitly is fine and dandy, but those

automatic transformation tools are limited and don’t yield nearly the

gains of explicit concurrency control that you code yourself. The

mainstream state of the art revolves around lock-based programming,

which is subtle and hazardous. We desperately need a higher-level

programming model for concurrency than languages offer today; I'll have

more to say about that soon.

Conclusion

If

you haven’t done so already, now is the time to take a hard look at the

design of your application, determine what operations are CPU-sensitive

now or are likely to become so soon, and identify how those places

could benefit from concurrency. Now is also the time for you and your

team to grok concurrent programming’s requirements, pitfalls, styles,

and idioms.

A few rare

classes of applications are naturally parallelizable, but most aren’t.

Even when you know exactly where you’re CPU-bound, you may well find it

difficult to figure out how to parallelize those operations; all the

most reason to start thinking about it now. Implicitly parallelizing

compilers can help a little, but don’t expect much; they can’t do nearly

as good a job of parallelizing your sequential program as you could do

by turning it into an explicitly parallel and threaded version.

Thanks

to continued cache growth and probably a few more incremental

straight-line control flow optimizations, the free lunch will continue a

little while longer; but starting today the buffet will only be serving

that one entrée and that one dessert. The filet mignon of throughput

gains is still on the menu, but now it costs extra—extra development

effort, extra code complexity, and extra testing effort. The good news

is that for many classes of applications the extra effort will be

worthwhile, because concurrency will let them fully exploit the

continuing exponential gains in processor throughput.